6 Collocation

Major Concepts

- Collocation and Co-occurrence

- Frequency and relative frequency

- Probabilistic properties of language

6.1 Quantities in corpora

In some sense Corpus Linguistics is really simple since it is largely focused on one basic indicator: frequency of occurrence. All annotations, such as lemma, pos, text type, etc. are ultimately measured in counts. There are hardly any other types of indicators, such as temperature, color, velocity, or volume. Even word and sentence lengths, are fundamentally also counts (of characters/phonemes, or tokens/words).

This simplicity, however, comes at a cost. Namely the interpretation is rarely straightforward. We’ve talked about how ratios become important if you are working with differently sized samples. I use sample here very broadly. You can think of different corpora as different samples, but even within the same corpus, it depends on what you look at. Let’s assume we were investigating the use of the amplifier adverb utterly. As a first exploration, we might be interested whether there are some obvious differences between British and American usage. For the British corpus, let’s take the BNC (The BNC Consortium 2007), and for the American corpus the COCA (Davies 2008).

> cqp

BNC; utterly = "utterly" %c

COCA-S; utterly = "utterly" %c

size BNC:utterly; size COCA-S:utterly

...

1204

4300The American sample returns more matches. Does that mean it is more common? No! The American sample is also about 5 times larger. We need to account for the different sizes by normalizing the counts. The simplest way to achieve that is by calculating a simple ratio, or relative frequency.

- \(\frac{1248}{112156361} = 0.0000111\)

- \(\frac{4401}{542341719} = 0.0000081\)

Now we can see that utterly actually scores higher in the British sample. We can make those small numbers a bit prettier by turning them into occurrences per hundred a.k.a percentages, which gives us 0.00107% and 0.00079%. That’s still not intuitive so let’s move the decimal point all the way into intuitive territory by taking it per million. utterly occurs 11.1 times per million words in the British sample and 8.1 times in the American sample.

Now how about the nouns utterly co-occurs with. To keep it simple, let’s focus on the British data.

BNC

count utterly by word on match[1]

...

34 and [#91-#124]

28 . [#20-#47]

27 different [#408-#434]

20 , [#0-#19]

13 at [#142-#154]

13 ridiculous [#929-#941]

11 impossible [#645-#655]

11 without [#1207-#1217]

10 miserable [#772-#781]

10 opposed [#820-#829]The two most frequently co-occurring adjectives are different and ridiculous. However, different is more than twice as frequent. Does that mean it is more strongly associated? No! The adjective different is itself also much more frequent than ridiculous (~47500 vs 1777).

6.2 Perception of quantities

Relative frequency and other ratios are not only interesting when you need to adjust for different sized samples. Human perception is also based on ratios, not absolute values. In some sense our brains also treat experiences on a sample-wise basis. Of course, you would not normally speak of experience as coming in samples, but remember the ideas of contiguity and similarity. We know that some of the structure in memory, therefore, structure in language, comes from spatially and temporally contiguous experiences, and/or the degree of similarity to earlier experiences. But of course we don’t remember every word and every phrase in the same way. Repetition and exposure to a specific structure play a key role. Now that we have a little experience with assessing what is relatively frequent in linguistic data, we should start thinking about what is frequent in our perception. An observation that has repeatedly been made in experiments is that absolute differences in the frequency of stimuli become exponentially less informative. This is captured by the Weber-Fechner law.

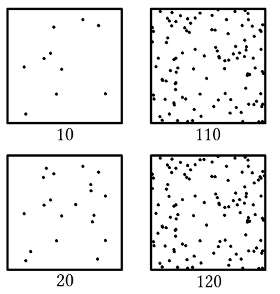

The observation is that the difference between 10 and 20 items is perceived as much larger than the difference between 110 and 120 items, even though they are the same in absolute terms. The higher the frequency of items, e.g. words, the higher the difference to another set has to be in order to be perceivable. This is strongly connected to the exponential properties of Zipf’s Law, which we will talk about in Week 7 and 8.

6.3 Collocation as probabilistic phenomenon

Collocations are co-occurrences that are perceived and memorized as connected. Some collocations are stronger, some weaker, and some are so strong that one or all elements only occur together, making it an idiom or fixed expression.

- spoils of war: idiom

- declare a war: strong collocation

- fight a war: weak collocation

- describe a war: not a collocation

- have a war: unlikely combination

- the a war: ungrammatical

The above examples are ordered according to the probability that they can be observed. We will get into the details of how we can quantify this exactly in the lecture and in future seminar classes. If you are impatient, www.collocations.de has a very detailed guide to how that works. For now, the logic is simply that we consider not only the different frequencies of the individual phrases, as in the examples above, but also the frequencies of the each word in the phrases, the words in the corpus, and all attested combinations of [] a war.

The important takeaway is that a defining property of collocation is gradience. That means that it is a matter of degree. The more frequent, a collocation is, relatively speaking, the more likely it is to be memorized as a unit. It is not a question of either or, or black and white. This idea has since been described for most if not all linguistic phenomena, including grammatical constructions, compound nouns, and even word classes, just to name a few.

6.4 Homework

Here is a gap filler. Use what you’ve learnt so far about frequency, corpora and CQP to fill in the gaps in a corpus-based approach rather than just using your intuition. Expert level: pick one of the association measures in the past papers (e.g. Mutual Information from Kennedy (2003)), and use it to provide options.

- I ______ forgot to call you.

- I have ______ shown you that the other day.

- This kid was ______ brave.

- It is _____ dangerous taking this way.

- Snow fell _____ outside.

- The Uni ____ recommends to wear a mask.

- It _____ ticked Alex off.

- The dinner was _____ tasty.

I’ll provide a walkthrough next week.

6.4.1 Tip of the Day

Like many other fields, English Linguistics has some standard literature that people cite a lot. A good starting point for any linguistic phenomenon are the big standard grammars. Huddleston & Pullum (2002) and Quirk (2010) are books that contain a lot of detailed descriptive information about anything English. They are also full of references for further reading. Some theoretical works that have been important in cognitive linguistics are Langacker (1999) and Goldberg (1995). If you are interested in metaphor, there is no way around Lakoff (1987) and Lakoff & Johnson (2008).

This is, of course, just a very limited selection. Make sure to consult any or all of those resources at least at some point during your own research for your term papers. Also don’t underestimate text books for students as a resource. It is not advised to cice from them, but they are also full of references, especially if you are exploring a topic and need descriptive information.