1 Introduction

Main goals of week one is to get comfy. We also want to refresh our memory about linguistics and get an overview about what is coming in the following weeks. I asked you why you picked morphology and what you expect from the class. We also discussed what questions are driving research in Lexical Semantics.

1.1 Linguistic questions

Throughout the course, we are going to discuss various topics mostly from—but not restricted to—the field of Lexical Semantics, e.g.:

- What makes an antonym?

- How do we determine useful collocations, phrases, synonyms?

- What is the relationship between meaning and grammar?

- How can we be objective about language?

- How does thinking shape language? How does language shape thinking?

1.2 The scientific process

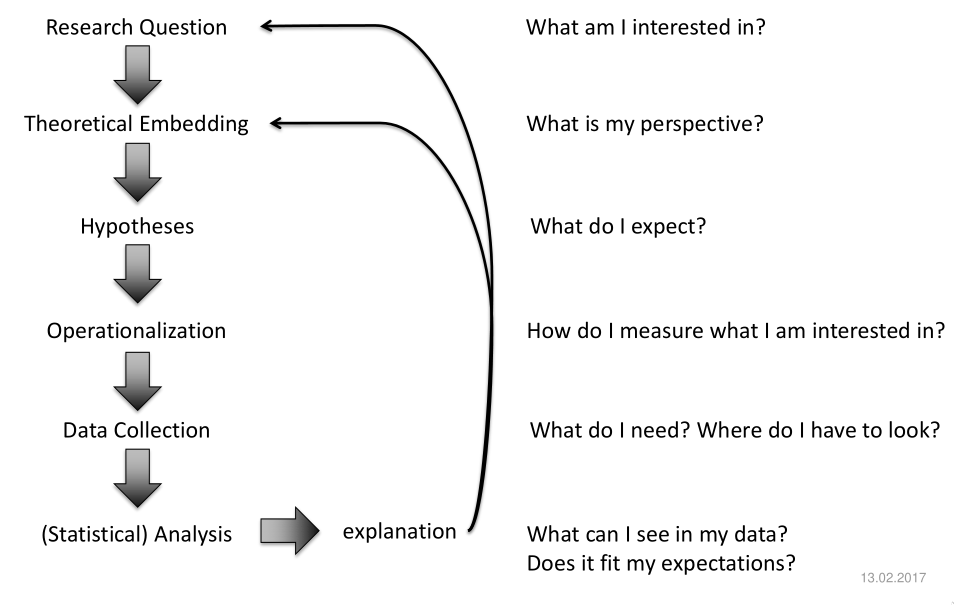

This week, we talked about the general process of carrying out a study in linguistics (or any other empirical discipline). The flow chart below depicts the scientific process. It does not only capture the steps involved, but also reflects the structure of the majority of academic papers in the field. Even if the sections in a paper aren’t called “operationalization”, etc., the methodological parts usually include a discussion of it.

Step one is always to find a research question, something that is important to the field of research and interesting to the researcher. In general, the more specific, the better. “How do speakers learn phrasal verbs”, is very broad; “how do learners of English learn phrasal verbs,” is still broad; “how are phrasal verbs used in student essays,” is better; “what phrasal verbs are underused in student essays”, is even better. The big questions can only be answered, if at all, by an entire field. An individual study has to be very focused, not only because of the practical requirements of small, time-constrained research groups, but also because of the amount of detail and scrutiny required. The topic above can even be narrowed down more. Most student papers suffer from having a research question that is too broad.

Next, the theoretical part practically requires two important steps. The existing literature has to be reviewed in order to explore, narrow down and define the concepts and the terminology necessary to approach the research question. It is also important to derive expectations that can be formulated as hypotheses. A hypothesis is no longer a vague question, but a very specific statement that can be falsified. Some research is purely exploratory, but most of the time, there are is a clear idea of what we expect to find in the data. Finally, we need to translate the theoretical concepts into measurable concepts. This step is called operationalization, i.e. making it possible to practically operate on an idea. Frequency of occurrence can be understood as theoretical concept describing the amount of times a phenomenon, e.g. a phrasal verb, is experienced by a speaker. In a study, we can only find indicators for this idea, so frequency of occurrence typically (and often implicitly) has an operational definition of frequency of occurrence in a text corpus.

It is important to note that this process is a feedback loop. If at any time, there are good reasons to step back, a researcher should and will go back. Often, if a concept is hard to measure, it is to complex which is a flaw in the conceptual design. Therefore, it might be necessary to go back to the stage of defining the concepts and formulating the hypotheses. If during the data collection new important variables are encountered, that weren’t predicted, it might be necessary to go back and think about how to systematically measure them (operationalize) or go back to the literature to see possible explanations and definitions of the concepts. Even as late as during the statistical analysis, a researcher might realize that they are asking the wrong questions. What is important is that the logic should not be reversed. Most importantly, the hypotheses shouldn’t be picked according to what the data can support. The research question shouldn’t be dictated by the available methods. The explanation derives from the theoretical framework, not vice versa.

Another more abstract model of research is the empirical cycle. It abstracts away the practical part of carrying out a study and is applicable to the general process within a field spanning many studies.

1.3 Course Aims

1.3.1 Linguistic and academic skills

The introduction course had the aim to provide you with the necessary terminology. Like in learning a language, you need to build up your academic vocabulary before you can productively participate in any discussion. This course now is the next step. We are going to transition from reading text book chapters to actual research literature. We are going to expand the concepts and the theory behind them. And finally we are going to put it to a test by writing a linguistic study.

In the end, you will…

- Have a deeper understanding of basic linguistic concepts

- Have first experience with reading and carrying out empirical research

- Understand basic concepts of cognitive science and usage-based linguistics

- Understand and compile basic statistics

1.3.2 Skills that go beyond linguistics

Many of the skills you acquire during this class are not only useful in linguistics. Especially knowledge of empirical methodology and statistics is now more important than ever. Everyone encounters results of empirical research (good and bad) on a daily basis on the news and social media, but too few people can actually interpret the information properly. Many jobs also require at least basic knowledge in statistics.

Furthermore, there are other skills that you may benefit from indirectly, such as…

- Understanding human perception of quantities

- Understanding memory

- Understanding non-linguistic research results better

- Improve writing, reading and computer skills

1.4 Homework

In order for everyone to get used to all necessary channels, I am not providing the readings, but rather make it your first task. A large part of our libraries resources is available digitally via the Campus network (eduroam) or from home via VPN.

- Setup a VPN connection to the university network.

- Download the main readings online and download them.

-

Google Scholar (you can search for authors by typing

author:name) - Primo

- Sometimes papers or entire books are uploaded on the authors own website, so regular search engines might help as well

-

Google Scholar (you can search for authors by typing

- Make a note for every reading you couldn’t find. Some require a bit of digging, but they are all out there.

Google Scholar even provides Primo links as long as you are connected to the university network (via VPN or eduroam). This makes finding literature rather effortless.

1.4.1 Tip

I’m going to share all sorts of productivity tips for the aspiring academic at the end of every homework assignment.

Today’s Tip:

Set up shortcuts to important search engines.

You will be doing a lot of research on Google scholar, Wikipedia, the OED, and so on.

Most browsers have functionality to make it easier for you.

Here is my setup:

In my address, bar I only type sc keyword or w keyword and my browser searches for ‘keyword’ automatically on Google scholar or Wikipedia respectively (combine with ctrl+l for hyperspeed 😉). 2 This works for most websites with a search field.

Here is where you find instructions for some popular browsers.

- For Firefox: Click here

- For Brave: Click here

- For Chrome: Click here