5.2 Perception of quantities

Relative frequency and other ratios are not only interesting when you need to adjust for different sized samples. Human perception is also based on ratios, not absolute values. In some sense our brains also treat experiences on a sample-wise basis. Of course, you would not normally speak of experience as coming in samples, but remember the ideas of contiguity and similarity. We know that some of the structure in memory, therefore, structure in language, comes from spatially and temporally contiguous experiences, and/or the degree of similarity to earlier experiences. But of course we don’t remember every word and every phrase in the same way. Repetition and exposure to a specific structure play a key role. Now that we have a little experience with assessing what is relatively frequent in linguistic data, we should start thinking about what is frequent in our perception. An observation that has repeatedly been made in experiments is that absolute differences in the frequency of stimuli become exponentially less informative. This is captured by the Weber-Fechner law.

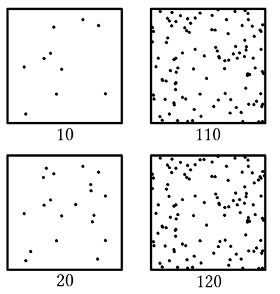

The observation is that the difference between 10 and 20 items is perceived as much larger than the difference between 110 and 120 items, even though they are the same in absolute terms. The higher the frequency of items, e.g. words, the higher the difference to another set has to be in order to be perceivable. This is strongly connected to the exponential properties of Zipf’s Law, which we will talk about in Week 7 and 8.